Politicians often demonise strangers, urging us to be cautious, to suspect those who come from different places or backgrounds. It’s a familiar message. Be wary, they say, of the stranger at your door, the unfamiliar face in your community. The call to fear is easy to hear and perhaps even easier to obey. Fear offers protection, or so we think.

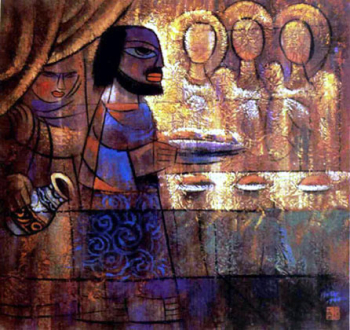

But prophets, those ancient voices still whispering across time, offer a radically different call. They invite us into the unsettling practice of hospitality, the willingness to welcome the stranger, not out of calculation or duty, but out of reverence for something larger. Hebrews 13:2 reminds us of the profound potential of this act: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by this some have entertained angels without knowing it.”

Angels. Messengers of the divine, slipping into our lives unnoticed, wrapped in the guise of strangers. It’s such a striking reversal from the political narrative we often hear, where the stranger is more likely to be seen as a threat than a blessing. But here, in the prophetic imagination, the stranger could very well be a source of grace, a bearer of wisdom, a gift in disguise.

What does it mean, then, to practice hospitality in this way? At its core, hospitality is not just about opening your home, but opening your heart. It’s about stepping into a space where control is loosened, where the encounter with another person—especially someone we do not know—can surprise us, challenge us, or even change us.

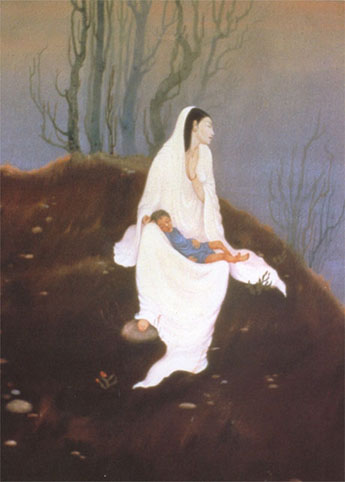

This is risky, of course. Hospitality always involves risk. When we welcome someone, especially someone unfamiliar, we make ourselves vulnerable. Vulnerable to discomfort, to difference, and to disruption of the familiar routines we cling to. But perhaps, in that very vulnerability, lies the possibility of transformation.

The ancient practice of hospitality is more than a social nicety. It is a spiritual discipline. It asks us to look past the convenient labels of “friend” or “enemy,” “insider” or “outsider,” and to see the other as fully human—worthy of care, dignity, and compassion. It beckons us to look deeper, beyond appearances and assumptions, to recognize the mystery and divinity hidden in the other.

In this way, hospitality becomes an act of faith. It means trusting that God works through the stranger, just as much as through the familiar. It means opening ourselves to the possibility that the person we are most inclined to fear might just be the one carrying a message of hope, or joy, or healing.

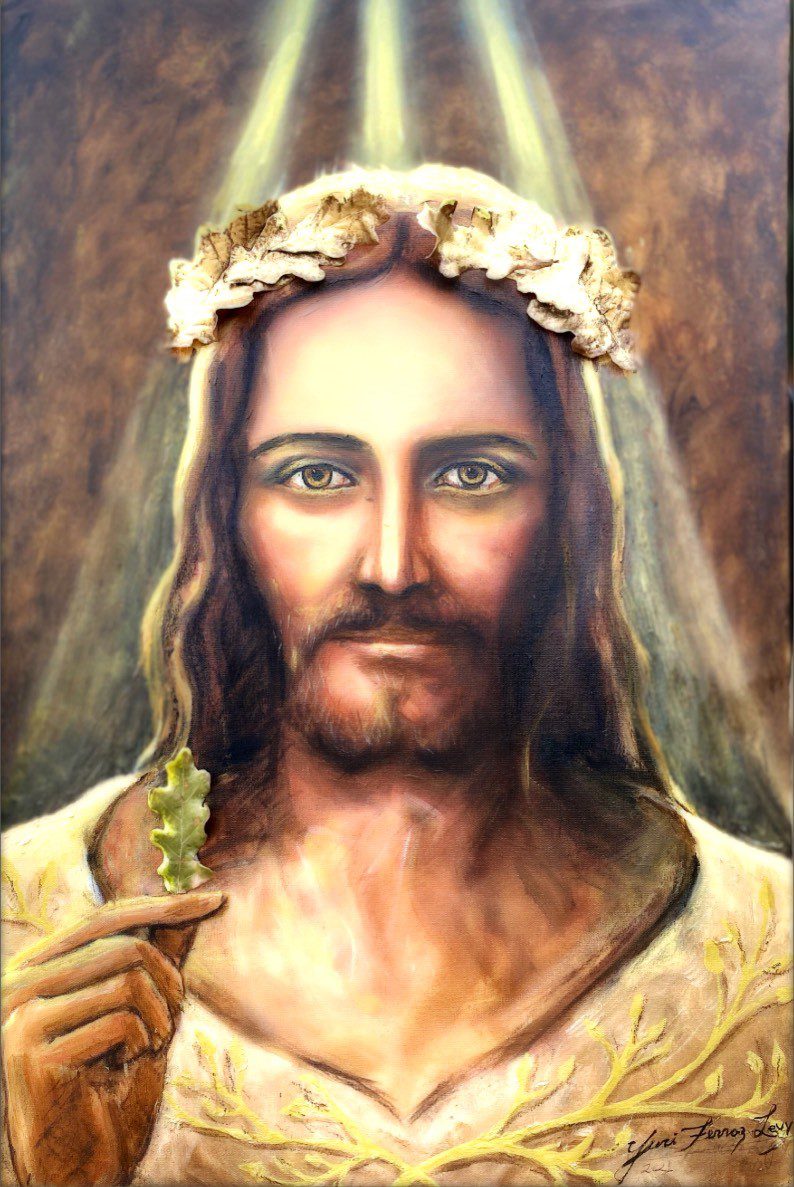

And isn’t this what makes hospitality so radical? It asks us to live in a posture of openness, to cultivate the kind of heart that sees beyond the surface, that looks for the sacred in the unexpected. It’s a way of living that resists the cynicism of the age, the fear that says “look out for devils.” Instead, it encourages us to imagine that angels might be nearer than we think.

This isn’t about naivety, of course. It’s not about ignoring the real dangers or challenges in the world. But it is about refusing to let fear be our dominant response to others. It’s about being people who live by grace, rather than suspicion, and who seek, in every encounter, the possibility of divine presence.

Perhaps, in showing hospitality to the stranger, we create space for God to surprise us. In that moment of openness—when we choose to see the other not as a threat but as a potential gift—maybe we find ourselves entertaining angels after all.

Leave a comment