I’ve been thinking a lot about claims that ethics is nothing more than a social construct—something we make up together, shaped by culture, time, and place. On some level, that makes sense. Different societies do have different values. What one group sees as honorable, another might see as offensive. If that’s true, though, it raises a hard question: can we ever really say another society is wrong? Do we have any right to criticize?

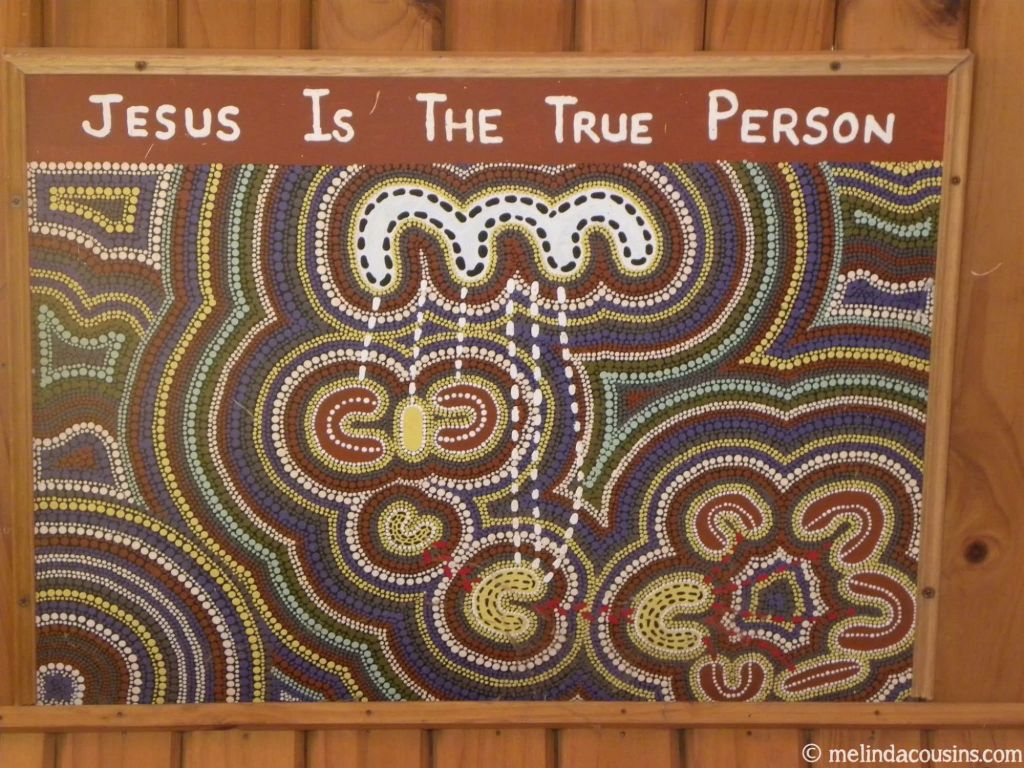

As someone shaped by a neo-Anabaptist perspective, I know I come to these questions with a particular lens. I don’t believe in moral neutrality. I believe Jesus calls us to live in a way that is radically shaped by his life, death, and resurrection—a way that refuses violence, embraces the marginalized, and tells the truth even when it costs us. That calling shapes how I think about ethics.

If ethics is only a social construct, then there’s no firm ground to stand on, even when confronting something like Nazi Germany. And yet, everything in me, and in the gospel I’ve come to trust, says that what happened there was evil. Not just “different,” but wrong. Systematically exterminating people because of their ethnicity or disability or perceived weakness isn’t just a cultural variation, it’s a deep violation of the image of God in humanity.

But I also have to be careful. As a neo-Anabaptist, I’m wary of moral superiority or coercive power. I don’t think we’re called to impose our values on others by force. I think we’re called to be a faithful presence, a living critique. Not by shouting people down, but by embodying another way. When we speak out, it should come from a place of humility and repentance, knowing that we’ve also been complicit in injustice.

So yes, I do believe there are limits to ethical relativism. I believe some things are wrong no matter where or when they happen, and I believe the life of Jesus shows us what goodness looks like. But I also believe that critique should never be about “us versus them.” It should always be about truth spoken in love, with the posture of a servant.

I guess, in the end, I don’t think we’re meant to be judges. We’re meant to be witnesses. And sometimes being a witness means naming evil for what it is. Not because we’re better, but because we follow a Lord who suffered under it, and who calls us to stand with those who still do.

Leave a comment