Frank Herbert’s Dune is not a Christian book. It offers no gospel, no grace, no risen Christ. But it may be one of the most important secular parables of our time for Christians trying to discern the dangers of Christian nationalism.

At first glance, Dune offers what many American Christians seem to long for: a messianic leader, born of prophecy, who rises to power, overthrows corrupt elites, and claims dominion in the name of the oppressed. Paul Atreides becomes the voice of a people dispossessed. He’s charismatic, righteous, and victorious.

But Dune is not about triumph. It’s about the tragedy of power disguised as salvation.

When a Messiah Becomes a Monarch

Paul Atreides is not a hero in the end. He is a cautionary figure, a messiah who unleashes a holy war he cannot control. His rise to power leads not to peace, but to jihad. Entire worlds burn in his name.

Herbert wrote Dune as a warning: beware of political saviors, especially those who wear the cloak of religion. The first novel seduces you with Paul’s strength, his vision, his justified vengeance. But in the end, we are left with a bitter truth: He won, and it was a catastrophe.

This arc should feel eerily familiar to Christians today, especially in America, where faith is increasingly harnessed for the pursuit of political dominance.

The Lure of the Political Messiah

Christian nationalism is built on a messianic narrative. It says America has a divine destiny. That Christianity must reclaim the land. That we need strong, godly leaders to purge the nation of evil and restore it to greatness. It sanctifies power. It spiritualizes politics. It wraps the cross in the flag and crowns the emperor in Jesus’ name.

But the gospel gives us no such king.

Jesus explicitly rejected this path. He told Pilate, “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight” (John 18:36). He entered Jerusalem not with armies, but on a donkey. He rebuked Peter for using a sword. He refused Satan’s offer of “all the kingdoms of the world” (Matt. 4:8–10).

The tragedy of Dune is that Paul Atreides says yes where Jesus says no.

Power, Prophecy, and the Illusion of Divine Destiny

What makes Dune so disturbingly relevant is how it portrays religion not as a force for humility, but as a tool of empire. The Bene Gesserit have spent centuries planting messianic prophecies across the galaxy, priming cultures to accept chosen ones when it suits imperial interests. Paul takes advantage of these legends, fulfills them, and becomes a god.

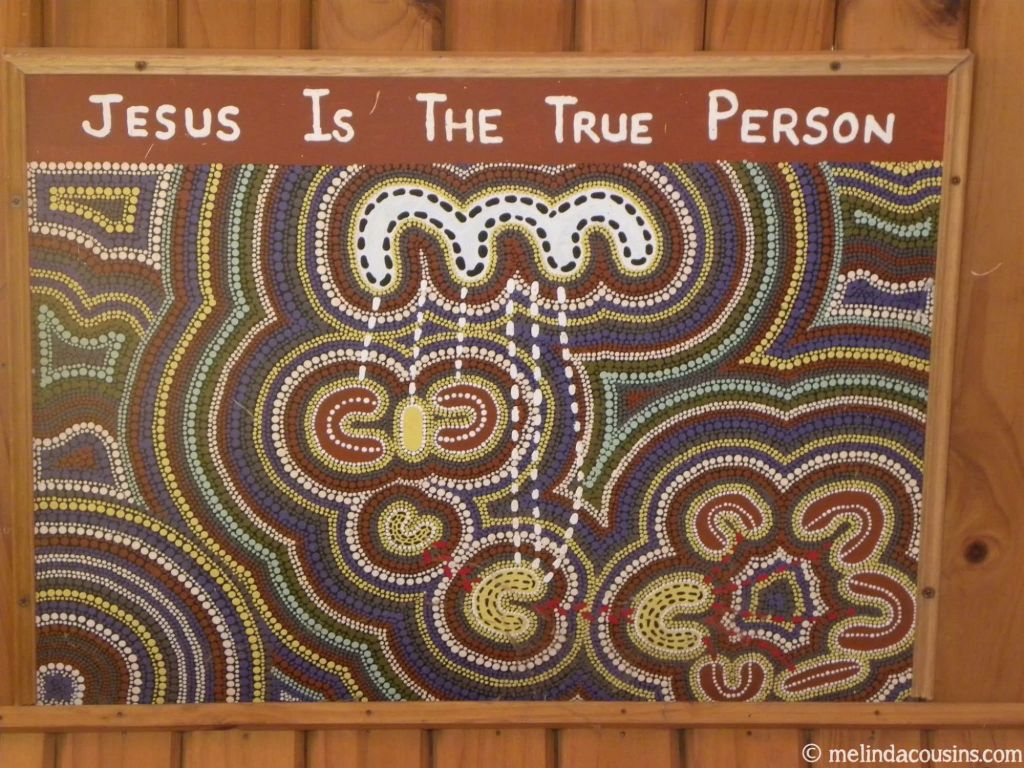

It’s all too easy to see parallels in how Christianity has been used to justify American expansionism, colonialism, and now, nationalism. Christian symbols are once again being wielded to sacralize state power, “anoint” political leaders, and energize culture wars under the illusion of divine mandate.

What Dune shows us, uncomfortably, is that even a true prophet can become a false messiah when power becomes the end. Even a justified cause becomes dangerous when pursued through conquest rather than cruciform love.

The Messiah Who Refused to Conquer

In Paul Atreides, we see a messiah who saves his people through domination. In Jesus of Nazareth, we see one who saves the world through surrender.

The American church faces a choice. Will we follow the way of Paul Muad’Dib—the path of conquest disguised as righteousness? Or will we follow the way of Jesus—the path of humility, enemy-love, and the cross?

If Christian nationalism is a revival of messianic politics, Dune is our mirror. It shows us where that path leads. And it should bring us to our knees.

Leave a comment