I’ve found myself increasingly uneasy with the way “public theology” is often done, even while remaining convinced that Christian faith can’t retreat into the private or the purely devotional. The unease isn’t about whether Christians should care about public life (we must of course) but about how we speak, what we assume, and whose terms we accept when we do.

Historically, public theology in Australia has often inherited habits from Christendom, even after Christendom has quietly died. Churches learned to speak to power, to offer moral guidance to the nation, to frame Christian convictions as broadly reasonable truths that everyone ought to recognise. That made a certain sense when Christianity functioned as cultural default. But in a plural, post-Christian, post-colonial society, that posture now feels strained. Too often it sounds like nostalgia dressed up as moral concern, or worse, an attempt to regain influence by translating the gospel into the language of policy, values, or “common sense” ethics.

Biblically, I struggle to see Jesus modelling that approach. He rarely tells Rome how it ought to govern, and he never appeals to abstract moral universals. Instead, he forms a people whose life together becomes a sign of another kingdom. His public engagement is unmistakable, even confrontational at times, but it is always grounded in his own identity and vocation. “If anyone wants to follow me…” is not a demand placed on the world but an invitation into a way of life. Even his sharpest critiques are aimed first at those who claim to represent God, not at outsiders who don’t share his story.

Systematically, this raises questions about where we think authority comes from. Much public theology leans heavily on natural theology or general theism, as though Christian ethics need a neutral foundation before they can be spoken aloud. I understand the impulse. It feels hospitable, reasonable, and less sectarian. But I worry that it subtly displaces Jesus from the centre. We end up arguing for positions that are defensible without him, and then wondering why our witness feels thin. If Jesus really is the revelation of God, then Christian public engagement should be unapologetically shaped by his life, teaching, death, and resurrection—not smuggled in at the end as a motivating footnote.

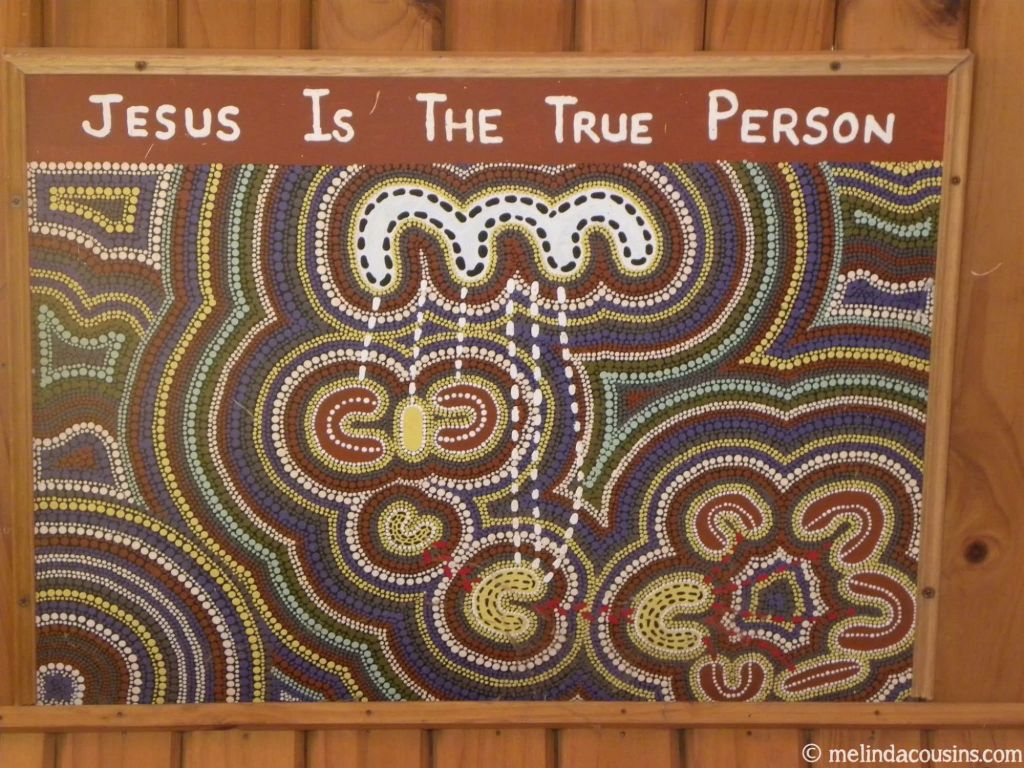

There’s also an epistemological question that nags at me, especially in Australia. Much of what passes for “public reason” is not neutral at all. It’s deeply shaped by Western, colonial ways of knowing. When Christians insist on speaking only in those terms, we may think we’re being inclusive, but we’re often just conforming to the dominant culture’s rules about what counts as serious or legitimate knowledge. That has consequences. Indigenous ways of knowing, communal and narrative forms of wisdom, embodied practices of truth-telling, these are all sidelined. The gospel, ironically, gets translated into the voice of the coloniser.

Practically, I’m more drawn to an approach that begins with a simple but demanding question: given the teachings and example of Jesus, how do we respond here? Not what should Australia do in the abstract, but what faithfulness looks like for Christians in this place, at this moment. That shifts the tone immediately. It replaces pronouncements with testimony, demands with confession, control with responsibility. It allows Christians to speak publicly without pretending to occupy some “neutral” moral high ground or to represent everyone else.

In the Australian context, this feels especially important. Our history of dispossession, our ongoing struggles with racism, our treatment of refugees, our instinct to reach for law-and-order solutions to complex social pain, all of these tempt Christians to grasp for power rather than to practice presence. A Jesus-shaped public theology won’t always sound “balanced” or “reasonable” by Canberra standards. It may look naïve, weak, or impractical. But it will be recognisable as Christian.

I’m not arguing for silence or withdrawal. I’m arguing for integrity. For a public theology that is less about winning arguments and more about telling the truth with our lives. One that resists the urge to speak for the nation and instead learns how to speak as the church: imperfect, located, accountable, and shaped by a crucified Messiah. If the gospel really is good news, it doesn’t need to be disguised as common sense. It just needs to be lived, and when necessary, spoken plainly.

Leave a comment