I am seeing a lot of Christians on the left spending a great deal of energy arguing for the innocence of Alex Jeffrey Pretti. I understand why. Bearing witness to innocence matters. Truth matters. The refusal to let lies be perpetuated by authorities is a profoundly Christian instinct.

But I think it’s important we recognise something uncomfortable: MAGA does not care. Or at least, not in the way we are assuming. So in a very real sense, it doesn’t matter whether Pretti can be proven innocent to the satisfaction of those in power. Not for what comes next anyway.

It is often said that Western cultures operate primarily within a guilt–innocence framework, while many Eastern cultures operate within an honour–shame framework. What is often forgotten is that there is a third cultural framework altogether: power–fear.

I want to suggest that the balance has shifted.

This is not to say guilt–innocence no longer matters, or that honour–shame has disappeared. All three are always present. But in this moment — particularly in the way the Trump administration is acting — power–fear has moved to the foreground.

This helps explain why appeals to innocence feel like they are disappearing into a void. Power–fear systems are not primarily persuaded by moral argument. They are concerned with dominance, deterrence, and the management of fear. “Officer safety,” “law and order,” and “restoring control” function less as legal claims than as assertions of authority.

Mark Carney spoke rightly that the old “rules-based order” is over. If so, then we need to be honest about what has replaced it. The operative rule now appears to be: might makes right. And that kind of power cannot be countered by appeals to innocence alone.

That does not mean innocence doesn’t matter. It means innocence by itself is no longer sufficient.

Waiting for legal procedure to catch up while people are being intimidated, detained, or killed is a recipe for failure. Legal processes still matter, but they tend to move only when forced to by pressure outside the system. History bears this out again and again.

If power is what is being exercised, then power is what must be confronted. But for Christians, there is only one form of power that can be faithful to Christ: people power, exercised non-violently.

This is not naïve optimism. The risk of civil war is real. The slide toward political violence is already visible. But non-violent mass mobilisation remains the most Christlike response precisely because it refuses to mirror the fear logic of the regime. It exposes it instead.

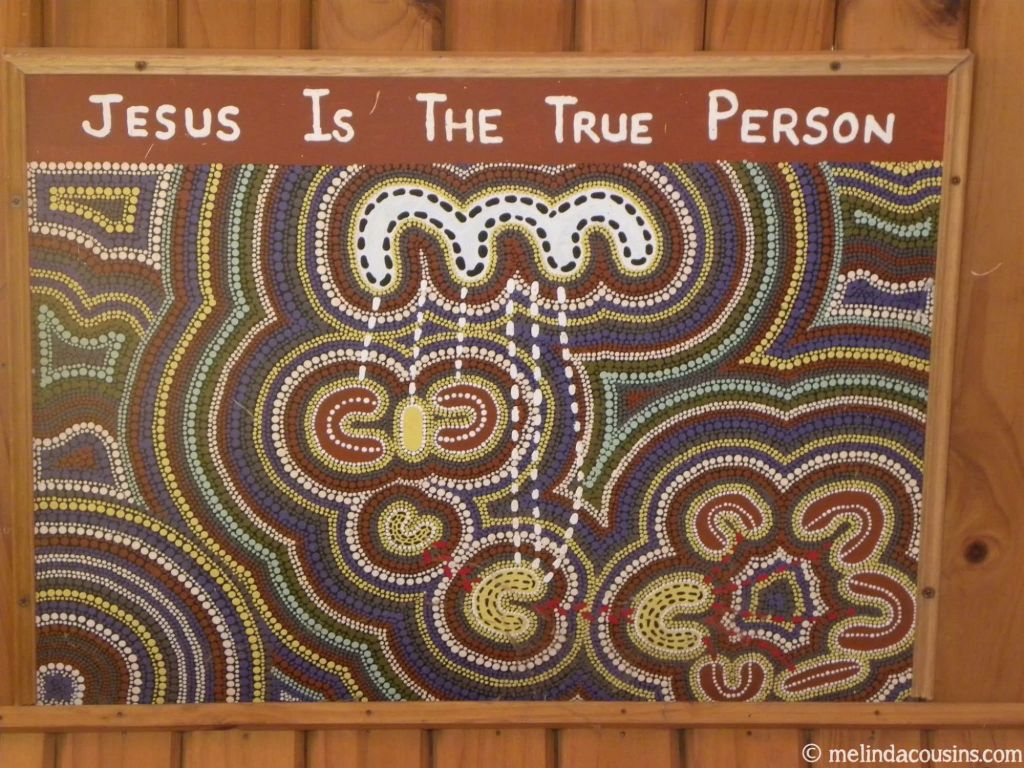

Theologically, this matters. Scripture does not operate within only one cultural frame. Guilt–innocence, honour–shame, and power–fear all appear throughout the biblical story. The Exodus confronts imperial power. The prophets shame unjust elites. The law names guilt. The cross gathers all three.

But power is decisively redefined in Christ.

Jesus did not deny power, he re-centred and re-framed it. Power is often framed in terms of domination, be he revealed a greater power in the capacity to give oneself without fear. At the cross, the power–fear system reached its apex and was unmasked as hollow. Rome can kill the body, but it cannot secure legitimacy, loyalty, or life.

Non-violent people power is not weak. It is cruciform. It does not abandon innocence; it organises it. It turns truth into pressure, and moral clarity into collective action. That is how power–fear regimes are actually undone — not by out-fearing them, but by refusing to be ruled by fear at all.

Leave a comment