Sometimes I wonder whether public theology is even a necessary category anymore. If we take seriously that the world, including the Western world, is a mission field, then all theology should already be public. Every act of faith is lived in relation to a watching world. Every church, every believer, stands as a witness within a wider culture. Why, then, do we still feel the need to treat public theology and missional theology as separate things?

I suspect this division has more to do with the legacy of Christendom than with the gospel itself. Within Christendom, “missional theology” was what we applied beyond our borders, while “public theology” was what we practised at home, as if the West were already Christian and the rest of the world were not. That framework assumes a centre and a periphery. We theologise for the world. They receive it. But in a post-Christendom society, that distinction has collapsed. The same tools we have long applied overseas (exegesis of culture, exegesis of scripture, evaluation, application) are just as necessary at home, where multiple cultures, subcultures and worldviews intersect.

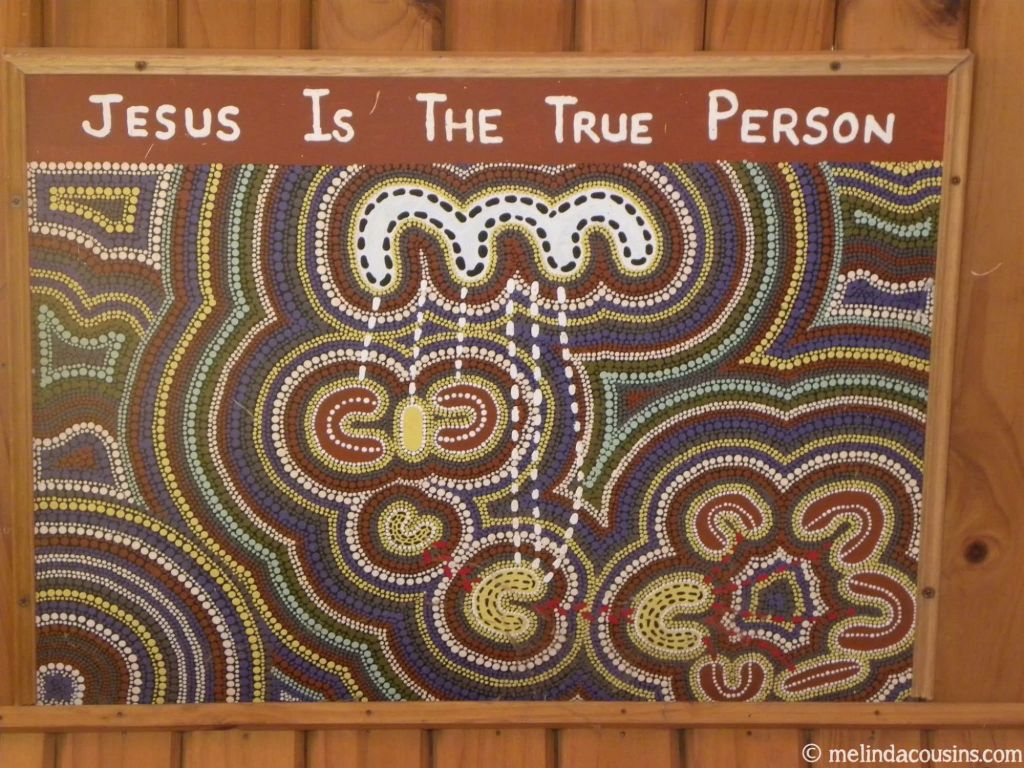

This is where I find the practice of critical contextualisation so helpful. In missiology, there is an awareness that whenever Christianity encounters a culture, it’s imperative to both affirm what can be affirmed and challenge needs to be challenged. It’s a two-way conversation: contextual and critically discerning at the same time. Yet strangely, many in the West assume this process is only necessary overseas. We critique African or Asian contextual theologies for the risk of “syncretism,” while seldom asking what forms of syncretism we’ve normalised in our own homegrown expressions of faith, whether consumerism, nationalism, or the idolatry of power.

If we really believe that no culture, including our own, has a pure, context-free grasp of the gospel, then the work of critical contextualisation must begin at home. And if that’s true, then what we’ve been calling public theology is simply a local form of missional theology. The difference is only one of geography, not of essence.

So perhaps it’s time to let the older categories go, or at least reframe them. Critical contextualisation becomes the method: discerning the cultural narratives that shape us, affirming what aligns with the gospel, confronting what doesn’t, and reframing the story of our lives and communities in Christ. The public square is just the arena: the social, political, and digital spaces where that recontextualised gospel and its practical implications are articulated. The task is not to defend a platform or claim prominence, but to inhabit these spaces faithfully, listening, witnessing, and participating in God’s redemptive work wherever we find ourselves. In this way, theology and mission are inseparable . Not as separate disciplines, but as a single, attentive, and incarnational engagement with the world.

Leave a comment